Feature: The FDA Accelerated Approval Program: A Double-Edged Sword

Jiyeon Joy Park, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Assistant Professor - Rutgers University Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Oncology - Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Piscataway and New Brunswick, NJ

Introduction

In 1992, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established the FDA Accelerated Approval Program in response to the HIV/ AIDS epidemic. Since then, the Program has allowed for faster approval of drugs for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need especially in the field of oncology.1, 2 Under the Program, drugs are approved based on surrogate endpoints, which could be laboratory measurements, radiographic images, physical signs, or other measures that are thought to predict clinical benefit, but are not a direct measure of clinical benefit.

In 2012, the FDA Safety and Innovation Act was passed, which required drugs approved through the accelerated approval pathway to have surrogate endpoints that are reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. Furthermore, the drugs approved through the Program need to demonstrate clinical benefit through confirmatory trials. If the confirmatory trial demonstrates clinical benefit, the FDA grants traditional approval for the drug. Otherwise, the FDA may withdraw the approval.1 While the Program makes for a speedy approval process that could be as short as a few months, there has been a significant number of application and indication withdrawals of targeted agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the recent months due to the failure to demonstrate benefit in confirmatory trials.2, 3

Accelerated Approvals and Withdrawals of Drugs/ Biologics in Oncology

According to Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) as of June 30, 2021, there were a total of 269 accelerated approvals for both oncology and non-oncology indications since the birth of the Program. More than 60% of these approvals were for oncologic indications, and the majority occurred just in the last 10 years. Most of the studies that led to accelerated approvals in oncology used either objective response rate (ORR) or progression-free survival (PFS) as a surrogate endpoint. Out of more than 180 oncology approvals, less than half of the approvals were successfully converted to full FDA approvals so far.3 To remind healthcare professionals, the package labeling of the approved products has a statement such as: “This indication is approved under accelerated approval based on overall response rate and duration of response. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s).”

One noteworthy example of a drug withdrawn after drawing attention for its initial promising results is olaratumab (Lartuvo). Olaratumab was originally approved for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) in 2016 based on the PFS benefit in a phase 1b/2 trial. It was widely expected to change the horizon of STS treatment by introducing a first-in-class targeted therapy for STS. However, olaratumab failed to demonstrate overall survival (OS) benefit in the confirmatory phase 3 trial (ANNOUNCE trial).4, 5 As a result, olaratumab was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer (Eli Lilly) in 2020.3, 5

The FDA has also requested manufacturers to withdraw their products if they failed to conduct confirmatory trials. For instance, the manufacturer (Sanofi-Aventis) for fludarabine phosphate (Oforta), never conducted the confirmatory trial due to lack of commercial demand and difficulty with subject recruitment. Subsequently, the FDA asked the manufacturer to voluntarily withdraw the product.3, 6

Accelerated Approval and Withdrawal of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

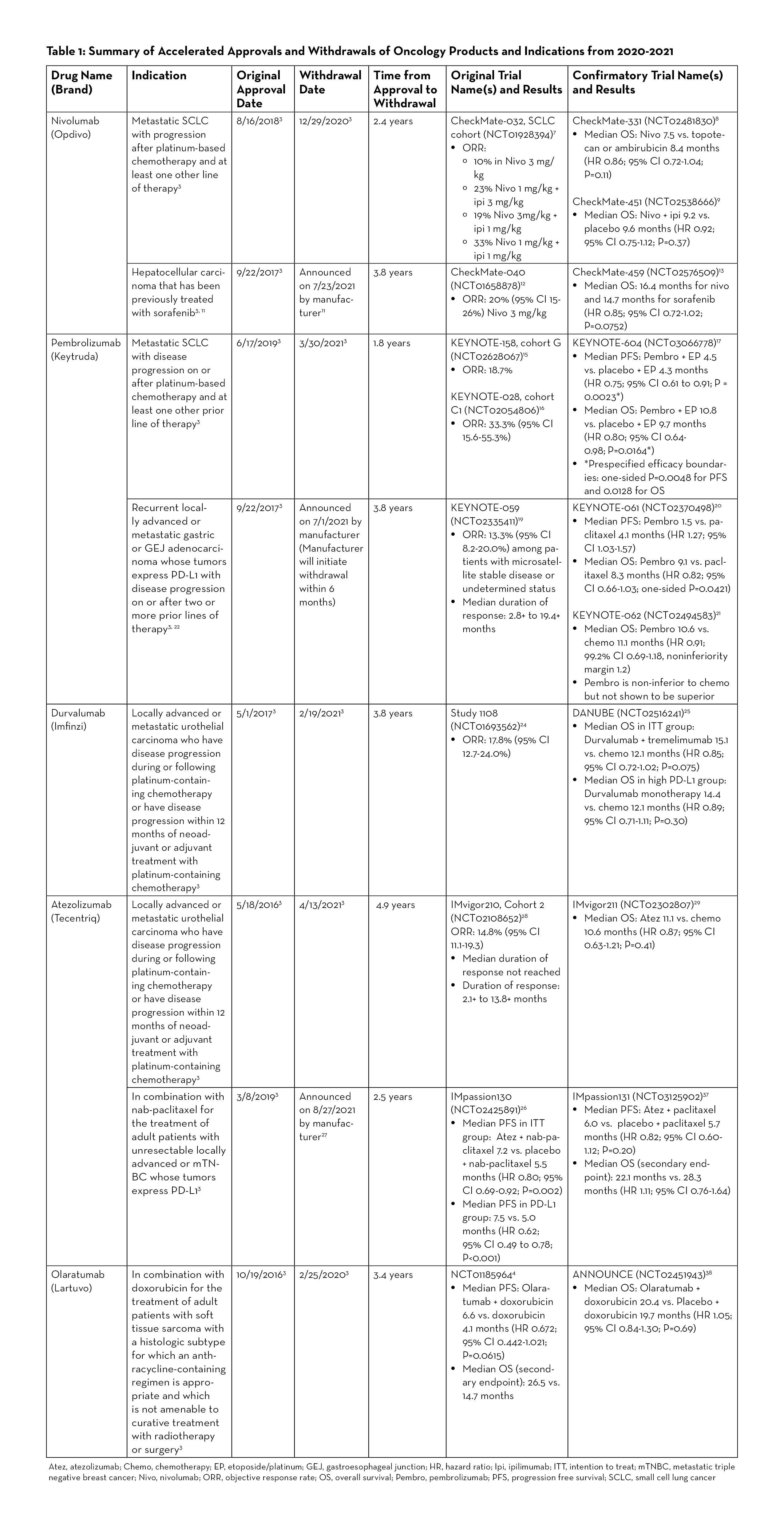

Since the advent of the Program, the FDA has granted accelerated approvals to various targeted agents, including many of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. According to CDER as of June 30, 2021, there were more than 50 approvals involving 8 immune checkpoint inhibitors—ipilimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab, atezolizumab, avelumab, cemiplimab, and dostarlimab. However, just in the last two years, there have been at least 7 withdrawals of indications involving immune checkpoint inhibitors, which is the greatest number of withdrawals at any given time since the beginning of the Program.3 Table 1 provides an overview of withdrawn oncology drugs/biologics from January 2020 to September 2021.

Nivolumab for Small Cell Lung Cancer

Nivolumab (Opdivo) was granted accelerated approval in 2018 for the treatment of patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) whose disease had progressed after platinum-therapy and at least one other line of therapy. The approval was based on the phase 1/2 CheckMate-032 trial studying nivolumab versus nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors.7 In the SCLC cohort, an objective response was observed in 10% of patients in the nivolumab 3 mg/kg group, 23% in the nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg group, 19% in the nivolumab 3 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 1 mg/kg group, and 33% in the nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 1 mg/kg group.7 In CheckMate-331, one of the confirmatory studies, there was no statistically significant difference in OS between patients who received nivolumab versus those who received topotecan or ambirubicin. The median OS was 7.5 versus 8.4 months respectively (HR 0.86; 95% CI 0.72-1.04; P=0.11).8 The other confirmatory study (CheckMate-451) also did not show OS benefit in nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus placebo (median OS 9.2 vs. 9.6 months, HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.75-1.12; P=0.37).9 As a result, the nivolumab indication for SCLC was withdrawn in December 2020.10

Nivolumab for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Nivolumab was initially approved in 2017 for treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who were previously treated with sorafenib. Recently, the manufacturer (Bristol Myers Squibb) announced that nivolumab would be voluntarily withdrawn after failing to meet post-marketing requirements in the confirmatory trial.11 The accelerated approval was based on tumor response rates in CheckMate-040, a multicenter, non-comparative, open-label phase 1/2 study. In the dose expansion phase of the study, the objective response was seen in 42 out of 214 patients (20%; 95% CI 15-26) receiving nivolumab 3 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks. Three patients had complete responses and 39 had partial responses.12 The confirmatory trial (CheckMate-459) in 2019 did not meet the primary endpoint of OS. The median OS was 16.4 months for nivolumab and 14.7 months for sorafenib (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.72-1.02; P=0.0752) which was not statistically significant.13

Pembrolizumab for Small Cell Lung Cancer

The results from KEYNOTE-158 (cohort G) and KEYNOTE-028 (cohort C1) studies led to the accelerated approval of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in 2019 for metastatic small cell lung cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other prior line of therapy.14 These two trials reported ORR of 18.7 and 33.3%, respectively.15, 16 KEYNOTE-604, the confirmatory trial, reported mixed results for the dual primary endpoints of PFS and OS. While the study met prespecified efficacy boundary for PFS, it did not meet the efficacy boundary for OS. Median PFS was 4.5 versus 4.3 months for pembrolizumab plus etoposide/ platinum (EP) and placebo plus EP, respectively (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.61-0.91; P=0.0023), and median OS was 10.8 versus 9.7 months (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.64-0.98; P=0.0164). The prespecified efficacy boundaries were one-sided P = 0.0048 for PFS and 0.0128 for OS.17 In March 2021, Merck, the manufacturer for pembrolizumab, announced voluntary withdrawal for the indication.18

Pembrolizumab for PD-L1-Positive Gastric or Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma

Pembrolizumab gained accelerated approval in 2017 for the treatment of PD-L1-positive recurrent locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma after two or more lines of therapy.3 The approval was based on KEYNOTE-059 study, an open-label, multicenter, non-comparative, multi-cohort trial, which demonstrated ORR of 13.3% (95% CI 8.2-20).19 In one of the confirmatory trials (KEYNOTE-061), pembrolizumab did not significantly prolong OS (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.66-1.03; one-sided P=0.0421). Median OS was 9.1 months for pembrolizumab versus 8.3 months for paclitaxel. Median PFS was 1.5 months and 4.1 months, respectively (HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.03-1.57).20 In another confirmatory trial (KEYNOTE-062), pembrolizumab was studied as monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy. While pembrolizumab was shown to be non-inferior to chemotherapy, it was not superior to chemotherapy. Median OS with pembrolizumab was 10.6 months versus 11.1 months with chemotherapy (HR 0.91; 99.2% CI 0.69-1.18, noninferiority margin 1.2).21 Merck, the manufacturer for pembrolizumab, announced on July 1, 2021 that it will withdraw pembrolizumab for this specific indication. Currently, pembrolizumab is still approved in combination with trastuzumab, fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy for patients with HER2-positive gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma.22

Durvalumab for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma

Durvalumab (Imfinzi) was granted accelerated approval in May 2017 for previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC), and the indication was voluntarily withdrawn by its manufacturer, AstraZeneca, in February 2021.23 The initial approval was based on Study 1108, a phase 1/2 trial which reported an ORR of 17.8% (95% CI 12.7-24.0%) in patients with locally advanced or mUC.24 The confirmatory trial (DANUBE trial) analyzed coprimary endpoints of OS compared between durvalumab monotherapy and chemotherapy groups in the population with high PD-L1 expression and between durvalumab plus tremelimumab and chemotherapy groups in the intention-to-treat population. The results demonstrated no significant OS benefit with durvalumab in both the high PD-L1 and the intention-to-treat populations. The median OS in the durvalumab monotherapy versus chemotherapy in the high PD-L1 group was 14.4 versus 12.1 months (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.71-1.11; P=0.30). The median OS in the intention-to-treat population was 15.1 in the durvalumab plus tremelimumab group versus 12.1 months in the chemotherapy group (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.72-1.02; P=0.075).25

Atezolizumab for PD-L1 Positive Metastatic Triple Negative Breast Cancer

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) was granted accelerated approval in March 2019 for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC) whose tumors express PD-L1 in combination with protein-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel). The approval was based on the phase 3 IMpassion130 study which demonstrated favorable PFS. In patients with PD-L1-positive tumors, the atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel group had median PFS of 7.5 months versus 5.0 months in the placebo plus nab-paclitaxel group (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.78; P<0.001).26 The subsequent confirmatory study (IMpassion131) did not meet the primary endpoint of PFS. Although the approval status was initially maintained after the FDA Oncology Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) convened in April 2021 and voted to keep atezolizumab, in August 2021, the manufacturer (Roche/Genentech) announced that it will voluntarily withdraw atezolizumab, stating that “…due to the recent changes in the treatment landscape, the FDA no longer considers it appropriate to maintain the accelerated approval.”27

Atezolizumab for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma

Atezolizumab received accelerated approval in May 2016 for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or mUC who have disease progression during or following platinum-based chemotherapy, or whose disease has worsened within 12 months of receiving neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy.3 The approval was based on the results of IMvigor210 study, which demonstrated ORR of 14.8% (95% CI 11.1-19.3%) in locally advanced or mUC patients who received atezolizumab 1200 mg IV every 3 weeks. The median duration of response not reached during the study.28 In the confirmatory trial (IMvigor211) published in 2018, the median OS was not shown to be statistically significant between the atezolizumab group and the chemotherapy group in patients with mUC who had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy.29 Subsequently, the FDA assigned another study as a confirmatory trial (IMvigor130); however, the manufacturer (Roche) decided to voluntarily withdraw atezolizumab as the second-line treatment of mUC.30 The data from IMvigor130 trial showed statistically significant PFS benefit in previously treated locally advanced/mUC patients; and while the interim OS data noted a positive trend, the full data analysis is pending.31 Atezolizumab still holds accelerated approval for the treatment of locally advanced or mUC patients who are not eligible to receive cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.32

Re-Approval after Withdrawal

Sometimes, withdrawn products have come back on the market after a modification of indications and/or warnings. For instance, gefitinib (Iressa) was on the market for 10 years since its accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), before it was withdrawn for its failure to demonstrate OS benefit. However, two years later, the FDA approved gefitinib for a more specific indication for the treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive NSCLC.33 In another example, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) was approved for the treatment of relapsed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients 60 years or older, but was withdrawn due to its failure to confirm clinical benefits and safety concerns including early mortality and veno-occlusive disease. It was re-approved years later at a lower dose for a different patient population (newly diagnosed CD33 positive AML patients).3, 34

Tracking Accelerated Approvals and Product Withdrawals

As many new drugs and biologics become approved, it may be challenging to keep track of the approval or withdrawal status of a product or an indication. The FDA publishes a summary report on drug and biologic accelerated approvals.2 In addition, the FDA ODAC conducts meetings to evaluate and review data concerning the safety and effectiveness of oncology drugs and make appropriate recommendations to the Commissioner of the FDA.35 Decisions on whether to maintain or withdraw accelerated approval of oncology drugs and biologics are made during the ODAC meetings, which are open to the public via webcast.36 The FDA also provides an email alert service (https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/contact-fda/get-email-updates) which sends out updates that can be tailored to oncology drugs and market withdrawals.

Conclusion

Surrogate endpoints do not always translate to clinical benefits or prolonged survival as observed in some of the oncology drugs/biologics approved through the FDA Accelerated Approval Program. Also, there seems to be highly variable amounts of time between accelerated approvals and the completion of confirmatory trials. The majority of withdrawals from the Program have so far involved oncology products, and immune checkpoint inhibitors have especially accounted for most of the withdrawals—perhaps due to a large number of accelerated approvals compared to other drugs and biologics. As much as the FDA Accelerated Approval Program brings in new therapy options and indications to the market with increased speed, healthcare professionals including pharmacists should also be vigilant of any approval status changes or withdrawals.

REFERENCES

- US Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves pembrolizumab for metastatic small cell lung cancer. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-metastatic-small-cell-lung-cancer

- Chung HC, Lopez-Martin JA, Kao SCH, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab in advanced small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): KEYNOTE-158. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15)doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.8506

- Ott PA, Elez E, Hiret S, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients With extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3823-3829. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5069

- Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo plus etoposide and platinum as first-line therapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-604 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(21):2369-2379. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.00793

- Merck. Merck provides update on KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) indication in metastatic small cell lung cancer in the US. Updated March 1, 2021. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.merck.com/news/merck-provides-update-on-keytruda-pembrolizumab-indication-in-metastatic-small-cell-lung-cancer-in-the-us/

- Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):e180013. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0013

- Shitara K, Ozguroglu M, Bang YJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10142):123-133. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31257-1

- Shitara K, Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone for patients with first-line, advanced gastric cancer: the KEYNOTE-062 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1571-1580. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3370

- Merck. Merck provides update on KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) indication in third-line gastric cancer in the US. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. https://www.merck.com/news/merck-provides-update-on-keytruda-pembrolizumab-indication-in-third-line-gastric-cancer-in-the-us/

- AstraZeneca. Voluntary withdrawal of Imfinzi indication in advanced bladder cancer in the US. Updated February 22, 2021. Accessed September 29, 2021. https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2021/voluntary-withdrawal-imfinzi-us-bladder-indication.html

- Powles T, O’Donnell PH, Massard C, et al. Efficacy and safety of durvalumab in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: updated results from a phase 1/2 open-label study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):e172411. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2411

- Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Castellano D, et al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):1574-1588. doi:10.1016/S1470- 2045(20)30541-6

- Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2108- 2121. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1809615

- Roche. Roche provides update on Tecentriq US indication for PD-L1- positive, metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Updated August 27, 2021. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2021-08-27.htm

- Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1909-20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4

- Powles T, Duran I, van der Heijden MS, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):748-757. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33297-X

- Roche. Roche provides update on Tecentriq US indication in prior-platinum treated metastatic bladder cancer. Updated March 8, 2021. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2021-03-08.htm

- Galsky MD, Arija JAA, Bamias A, et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1547-1557. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30230-0

- Tecentriq (atezolizumab) [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech Inc; 2021.

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 206995Orig1s000 summary review. Updated July 13, 2015. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/206995Orig1s000SumR.pdf

- US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves gemtuzumab ozogamicin for CD33-positive AML. Updated September 1, 2017. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-gemtuzumab-ozogamicin-cd33-positive-aml

- US Food & Drug Administration. Oncologic drugs advisory committee. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/human-drug-advisory-committees/oncologic-drugs-advisory-committee

- US Food & Drug Administration. October 28, 2021: meeting of the oncologic drugs advisory committee meeting announcement. Updated September 3, 2021. Accessed September 30, 2021.

- Miles D, Gligorov J, Andre F, et al. Primary results from IMpassion131, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase III trial of first-line paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab for unresectable locally advanced/ metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(8):994-1004. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.05.801

- Tap WD, Wagner AJ, Schoffski P, et al. Effect of doxorubicin plus olaratumab vs doxorubicin plus placebo on survival in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: the ANNOUNCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1266-1276. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1707